About the Author

Sri T.V Kapali Sastry (1886-1953) was a multiple personality. He excelled in whatever field he worked. Among his several services to the national heritage, the one which comes most prominently to the mind is his solid contribution in building a strong bridge between the ancient past and the evolutionary thought of the present. Following the trail of his masters, first of Vasishtha Ganapati Muni and then of Sri Aurobindo, he unearthed many a truth that underlies concealed within the cryptic utterances of the Veda. In the great adventure of reinterpreting Vedas to us along the lines of Sri Aurobindo, Sri Kapali Sastry played a significant part.

Sri TVK’s writings on the Upanishads, especially on the various Vidyas, disciplines, that are described briefly and cryptically in the originals, are a treasure of mystic lore.

Sri TVK’s writings are in four languages namely English, Tamil, Telugu and Sanskrit. Sanskrit was more natural to him. All his writings are collected and published in eleven volumes.

Sri TVK regarded himself as a Tantrik, first and last. He was a profound votary and a masterful adept in the mantra shastra. It is on record how his Mantra Japa turned the tide in the lives of many in distress.

One of the great contributions of Sri TVK is to dispel the myth that the various Hindu Scriptures like the Veda Samhitas, Upanishads, Yogas, Tantras etc. are disparate and do demonstrate that they compliment one another.

Preface

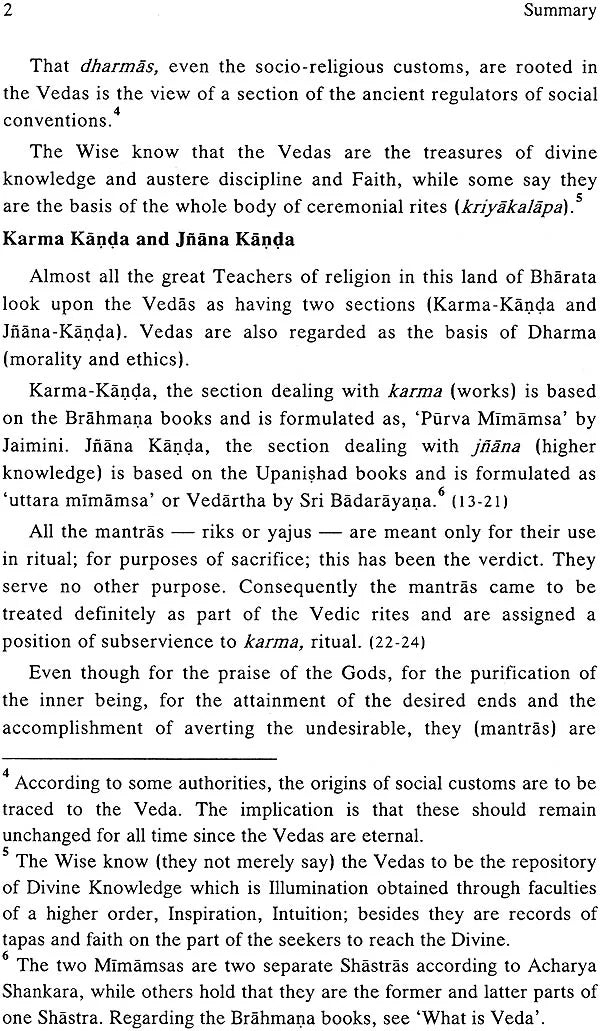

This commentary on the Rig Veda of which the first ashtaka is now published starts with the bhumika _ a long introduction in which the line of esoteric interpretation as shown by Sri Aurobindo is expounded. A summarized version of the same in English was published some time ago. In this foreword, I should like to explain how I happened to undertake this sacred task. In the translator’s preface to my Tamil rendering of the Hymns to the Mystic Fire I made a statement, the substance of which I give below.

In the nineties of the nineteenth century when, according to the family custom, I was being taught the chanting of the Veda-sama gana with the rik-texts, I had a vague idea, a strong belief characteristic of old style orthodoxy that Veda means Veda-purusha, it is God as Veda, eternal, the sound-body of God. Beyond this I did not think and could not. When a few years later, I grew in knowledge of Sanskrit just enough to read and understand the simple and lucid commentary of Sayana, I was curious to know at least the meaning of those riks which I had already got by heart. When I turned to the pages of Sayana-bhashya I did not find any difficulty in understanding the word – for – word meaning given therein, but in some places I Vaguely thought there was something more than what was written there, but I was not able to go further; what little I could sense was that it was dark to me and the darkness was visible; in effect my eyes could not see. A few years afterwards it was the late Vasishta Ganapati Muni (1878-1936) – Kavyakantha Ganapati Sastri, whom we adored and addressed as Nayana, (beloved father) – who in a way first opened my eyes. It was he who since 1907-1908 took me as his own and guided me in many branches of Sanskrit study and laid in me the foundations for spiritual life which in later years grew to claim me in its entirety. It was in 1910 that he favoured me with instructions regarding the Deities of the Rig Veda and depth of thought in the Vedic hymns.

But from 1914, ever since the Journal arya began to appear I have closely followed Sri Aurobindo’s approach to the study of the Rig Veda and whole- heartedly, with sufficient reasons, accepted it. It is not that I rejected Vasishta Muni ‘s method in order to accept Sri Aurobindo’s. For while it is a fact that he took up stray hymns on accasions, explained them, taught us to appreciate the grandeur, beauty and wealth of ideas in the hymns, he did not write a commentary on even an anuvaka or a small portion of the Rig Veda. Nor did he work out a method of interpretation. There was indeed enough of original thinking and inspired talks he gave us in plenty. One remarkable fact is this: both Sri Aurbindo and Sri Vasishta Muni came to extraordinary conclusions about Vedic Gods and Vedic secret independently without the one knowing the other. Their methods are not identical, their views are not the same, though both regard the Veda in supreme esteem as a scripture of secret Wisdom. The latter closed his earthly career without committing to writing the results of his Vedic studies.+ since I have made reference to these Vedic studies of Vasishta Muni in some of my Sanskrit works including his biography and commentaries on his poems, since I am also closely associated with the Teachings of Sri Aurobindo and in particular a commentator on the Rig Veda along his lines, there is likely to be a misconception. To make the position clear is the relevancy for this personal note.

Nearly ten years ago (around 1940) some friends here asked me to give word-for-word meaning in simple Sanskrit for Rig Veda hymns so that they could be rendered easily in Hindi afterwards. I thought it could be done, but thought also that it would not be acceptable to scholars in the absence of necessary explanations, grammatical notes, justification for departure where necessary from old commentaries or modern opinion. So I placed the matter before Sri Aurobindo with my submission that I would undertake the task only if he would be pleased to go through what I write. This he graciously agreed to do and added that I could write the commentary keeping close to his line of interpretation and using the clues he has provided to unveil the symbolic imagery for arriving at the inner meaning that is the secret of the Veda.

With his blessings, then, I started the work. As it was proceeding, I placed it before him in convenient parts for perusal at his pleasure. This commentary has received his general approval and the benefit of his occasional suggestions and remarks that have enabled it to keep more and more close to the spirit of his interpretation. But I am fully responsible for all that is written in the commentary, including details, regarding the fixing of meanings for certain words which lend themselves to different interpretations. I have generally taken Sayana for my model, in regard to word-for-word meaning, grammar, accent etc., though necessarily there is departure in regard to the drift of the hymns and in some places, the construction of sentences. I have not mentioned the viniyoga, the application and use of the mantra in particular rites; for that would be necessary if the present work were to explain the symbolic character of the Vedic rites. But that is beyond the scope of this commentary.

I had thought of recording and comparing the opinions of other commentators as far as available and at one time thought of making references to the opinions of modern scholars, especially of the West, who have made no mean contribution to Vedic studies, with the help of comparative philosophy with all its shortcomings, particularly in regard to the fixing of the meaning of words. But after deliberation and consultation in proper quarters, I found it advisable to confine myself to what I had to say positively, in view of the purpose of the commentary which is to expound the inner sense and not to encumber the work with the views of other authorities and increasing it in bulk involving enormous labour that might entail the risk of not completing the printing even of the first ashtaka.

As the commentary was progressing, the thought occurred to me, that in the absence of a background, both the modern scholar and the old type pundit alike would be at a loss to follow the meanings and explanations given in the commentary. Therefore the bhumika was written explaining the position and examining it in the light of scriptural texts ranging from the Vedas down to the puranas.

Thus the first hundred pages of the book were separately taken out from the printed forms and sent out to pundits, scholars for opinion. The response was generous, almost unanimous and encouraging. If there was a note of hesitancy anywhere in the opinions, it was this: can all the hymns or the majority be shown to bear out the esoteric sense? This is certainly a genuine doubt, revealing at the same time a certain openness to accept the esoteric interpretation if the hymns are systematically shown to contain the sense we plead for.

This commentary, it is hoped, answers to the demands of the discerning mind.